Falstaff

Giuseppe Verdi

Libretto by Arrigo Boito

based on William Shakespeare's plays

The Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry IV parts 1 and 2

Friday, May 24 - 8 p.m.

Sunday, May 26 - 2 p.m.

Saturday, June 1 - 8 p.m.

Sunday, June 2 - 2 p.m.

at the Lucie Stern Theatre

1305 Middlefield Rd., Palo Alto, CA 94301

Performances are 2 1/2 hrs long, including 2 intermissions.

FREE Preview with Piano

Thursday, May 16, 2019 - 8:00 p.m.

Palo Alto Art Center

1313 Newell Rd., Palo Alto, CA 94301

About Falstaff

World Premiere: Teatro alla Scala, Milan - Feb 9, 1893

WBO Premiere: May 11, 1984

Pictured: interior of the Teatro alla Scala - Milan

Falstaff was Verdi's second and last joint project with Arrigo Boito (the first was Otello), who adapted Shakespeare's The Merry Wives of Windsor into the libretto, also incorporating several scenes from Henry IV , parts 1 and 2. The score is like nothing else he wrote. Verdi really captures the essence of Sir John Falstaff's character: a man so essentially full of himself that he manages to take credit even when he is the object of humiliating public ridicule. Verdi relished the opportunity to write a comic opera (only two of his twenty eight operas were comedies), and produced a witty, dynamic and elegant piece like no other in the entire operatic repertoire.

Creative team

Cast

Bardolfo (M. Orlisnsky), Nannetta (A. Malliaras), Ford (K. Karagiozov), Alice (T. Haines), Fenton (D. Suarez), Caius (M. Mendelsohn), Mistress Quickly (P. Houston), Pistoa (K. Havezov) and Meg (V. Jensen)

Falstaff (R. Zeller) and Mistress Quickly (P. Houston).

Ford (K. Karagiozov)

Ford (K. Karagiozov) and Falstaff (R. Zeller)

- Read the review in the Melbourne Sun and Opera Chaser

by Paul Selar

Across centuries of storytelling through opera, the position of and outcomes for women rarely look glowing for contemporary eyes. Even when holding positions of power, they draw the short straw, often depicted with an emotional fragility and doomed by the men around them.

But over the course of a day in Verdi’s Falstaff, based on the larger-than-life character from three of Shakespeare’s plays - The Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2 - women appear to have the upper hand. In its comic comment on entitlement, lechery and gluttony focused on The Bard’s “great whale of Windsor”, Falstaff is outsmarted and mocked after plotting to seduce two married women who want to teach him a lesson. Indeed their cheeky retaliatory efforts go to plan but does Falstaff learn his lesson? Sadly, he seems not to have, for this hard-shelled self-assured mass ignorantly believes himself victorious.

In watertight dramatic form, Shakespeare’s intriguing plot is jauntily and snugly bound to Verdi’s swift-paced and narrative-heightened music and in tune with Arrigo Boito’s comically-polished and visually inducing libretto. It also comes staged in a fantastical and quirky period staging by Mexican director Ragnar Conde with a strong singing/acting cast from a company I had the fortune of discovering recently on a trip to San Francisco.

Smack in the land of small start-ups and global technology companies, Palo Alto’s West Bay Opera is a treasurable find. The company are celebrating their 63rd season in what is a modest 400-seat theatre that feels too small than the level of artistry on show. It also seems the company have been in the business of delivering high quality opera for decades judging by photos of previous productions hanging in the lobby of the Lucie Stern Community Theatre.

Running the operation, Artistic Director and conductor José Luis Moscovich has assembled a genuinely unified cast sporting fine credentials. He also keeps the vitality and momentum of Verdi’s score well-oiled and shapely in a challenging three-level arrangement of the near 30-member orchestra. Despite a slither of the stage being utilised uniquely to house the brass section on two levels due to pit limitations, it works a treat. Notably, while presiding over strong musicianship, Moscovich shows himself to shine as a singer’s conductor and together with Conde, creatives and artists, all the boxes get ticked for a meaty and hugely entertaining encounter.

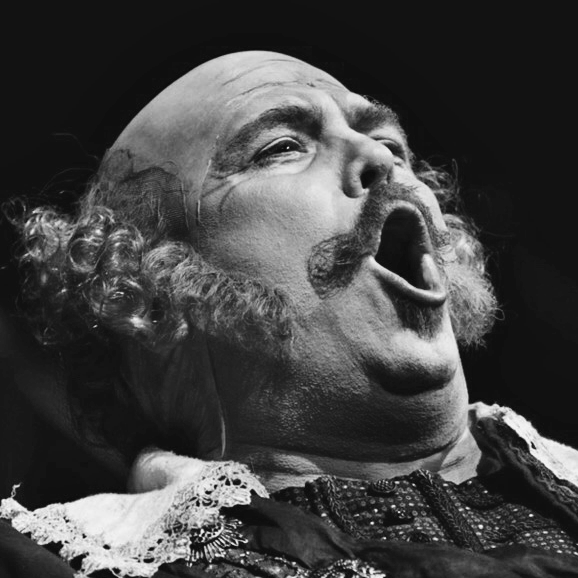

Watching and hearing the molten and smoky baritone blend of Richard Zeller’s Falstaff celebrating his belly and getting a good roasting is theatrical gold. An experienced Metropolitan Opera singer, Zeller’s animated and agile Falstaff prompts laughter both with him and at him, with continual lashings of charisma and spots of sympathy for the ridicule he receives. Zeller makes his performance all the more impressive because every moment on stage is given conviction as Falstaff engages, dismisses, plays and grapples with his townsfolk.

Taylor Haines delivers assurance that Alice Ford - object of Falstaff’s lust for her body and her money - has what it takes to enact her trap for Falstaff, weighting her plush and flexible soprano superbly to the text and dishing out elegantly projected top notes. Haines is joined in spirited form by gem-studded mezzo-soprano Veronica Jensen as Meg Page. Complicit in their trickery, Patrice Houston swirls about in generous vocal richness accompanied by deep plunging humour as Mrs Quickly. As Alice’s darling daughter Nannetta, Anastasia Malliaras’ sparkling soprano improved from thoroughly delightful early on to excellence in Act 3’s beautifully floated gossamer-edged fairy song. As her young lover, Dane Suarez’s warm tenor comfortably fits his ardent Fenton.

Michael Mendelsohn’s fine characterful rawness as a dishevelled Dr. Caius, together with Falstaff’s thieving double-crossers - Michael Orlinski’s limber Bardolfo and Kiril Havezov’s brawny Pistola - effortlessly humorise in setting the scene for trouble ahead. Completing the ensemble of nine solists as Alice’s distinguished husband Ford, smooth and muscular baritone Krassen Karagiozov gives jealousy a handsome touch. A small exuberant chorus of townsfolk and fairies fill out the picture evocatively.

Then there is the absolute joy derived from the staging itself. The striking beauty, subtle playfulness and sophistication of Peter Crompton’s combined projections and set-build are utterly absorbing. In its implied Elizabeth-era setting, with striking, detailed costumes by Abra Berman and a cocktail of lighting by Steve Mannshardt, stepped and wandering spatial interest provide ample opportunity for Conde’s lively direction on a restricted stage. King timbers angle in expressionist boldness. Infill walls and backgrounds give modern technology and creativity a canvas for all sorts of wondrous imagery, including a monster’s open mouth in the form of roaring fireplace in Acts 1’s Garter Inn within which a pig is being roasted on the spit. Obvious?

In this all-round accomplished West Bay Opera production, symbolic mockery is comically kept alive with everyone and everything out to punish Falstaff. Perhaps his only defenders sit somewhere in his audience. Now that’s a recipe for debate!

Falstaff

West Bay Opera

Lucie Stern Theatre, Palo Alto

Until 2nd June, 2019

This and other reviews by Paul Selar are available at

http://operachaser.blogspot.com/2019/05/a-fantastical-and-quirky-period-set.html

- Read the review in forallevents.info

by Victor Cordell

Falstaff holds a unique position among Verdi’s operas. It was his final work and one he toiled over for several years. With the exception of the failed and barely mentionable early work, Un giorno di regno, it was his only comedy. And musically, while it lacks “Top 40” hits, the score is highly inventive. The composer incorporates all the tricks from a lifetime of musical mastery and adds some more. His variation of texture and rhythm are pronounced and especially realized in ensemble pieces.

We are fortunate that smaller opera companies in the Bay Area take risks in producing outside of the old war horse catalogue, and comedies like Falstaff present particular challenges. Timing of delivery, accuracy of expression, enthusiasm of affect, and versatility of voice all must be heightened. However, one advantage of performing in a smaller house is that the necessary exaggeration is more visible to the audience. As a result of excellent casting, attractive visuals, and fine musical and stage direction, West Bay Opera offers a special treat with its glorious Falstaff, based on Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor, with libretto by the distinguished Arrigo Boito.

Verdi admired Shakespeare and had successfully adapted the Bard’s work, early in his career with Macbeth, and much later with his penultimate opera, Otello. Although the dark tone of Otello sharply contrasts with the brightness of Falstaff, the former acted as a musical precedent to the latter with its through-composed form. With this format, no melodic repetition occurs. So in the absence of set pieces with memorable tunes, the ear is treated instead to endless anticipation and variety.

Verdi was no doubt drawn to the bigger-than-life character of Falstaff. Lecherous and self-indulgent, he is one of the great comic characters from literature. Today, he can be viewed as a social throwback in the context of the #Me Too Movement. Although he didn’t abuse power of position to entrap women, he did use inducement and deception to compromise them, and in the vernacular, he was simply a dirty old man.

The sum of the central plot is that Falstaff sends love notes to two married women, Alice Ford and Meg Page, who are friends and learn of the duplicity. They turn the tables on the perpetrator who is duly spurned and humiliated. A secondary plot is that Master Ford has arranged for their daughter Nannetta to marry the older Dr. Caius, but she loves and pursues the young Fenton. The momentum of the story is a little slow to develop, and by the time closure arrives, it seems to drag a bit. But it moves along nicely during the bulk of the action with great energy.

The dominant tone of the music is lively and punctuated by a number of highly animated, rapid ensemble pieces such as the complex women’s a capella patter quartet in which they vow revenge against Falstaff. Another highlight is the more complicated double quartet in which men sing of their search to foil the young lovers Fenton and Nannetta, while the women show support for them, and the lovers sing above the fray. These brisk ensembles are delivered with remarkable skill and aplomb.

Some aria-length solos occur, which are often reflective, particularly Ford’s wonderful soliloquy about his love for Alice. But in keeping with his new direction, Verdi does not yield to recurring melodic phrases which mark the beloved arias of his middle period. While this may disappoint some listeners, Falstaff is a masterpiece within its paradigm.

The cast of the production excels from top to bottom. The success of the production rides first on the able shoulders of Richard Zeller, a classic Falstaff. With the aid of costumery, makeup, and wig, he looks the part of the corpulent rogue, but his commanding presence and ebullient acting yields the required brio and debauchery. Of course, the proof of the pudding is in the singing, and Zeller charms with a playful high end, a strong and clear middle, and a resonant low.

Another fine performance comes from Taylor Haynes, a talented lyric soprano on the ascent who sings Alice Ford with a warm yet penetrating voice. An entertaining role in some operas is a contralto servant type who is a nanny or maid. The proxy for that type in Falstaff is the mischievous Mistress Quickly, and Patricia Houston nails the characterization. Finally Conductor José Luis Moscovich orchestrates the elaborate musical elements with total command.

Cast.

Staging is highly effective given physical constraints of the performance site, with Stage Director Ragnar Conde coordinating the piece. Set Designer Peter Crompton and his Projection Co-Designer operate from a previous stage template with columns, step-ups, and back-lit projections. This version works particularly well with a variety of backdrop imagery, some of which provide visual depth to the stage as well. Abra Berman’s exquisite costumes for principals and chorus not only satisfy the need to clothe performers in period garb, but they add a welcomed visual dimension to the stage.

Falstaff with music by Giuseppe Verdi and libretto by Arrigo Boito is produced by West Bay Opera and plays at Lucie Stern Theatre, 1305 Middlefield Road, Palo Alto, CA through June 2, 2019.

Read this and other reviews by Victor Cordell at

http://forallevents.info/reviews/falstaff/

- Read the review in Talkin' Broadway and theatreeddys

Saturday, May 25, 2019

"Falstaff"

Falstaff

Giuseppe Verdi, with Libretto by Arigo Boito

West Bay Opera

“In this great abdomen are a thousand tongues that proclaim my name ... This is my kingdom.” With a measure of self-worth and a confidence in his own attraction to the fairer sex that are almost as mammoth as his rotund belly, Falstaff sings with from his tavern bench as if it were his royal throne. In Giuseppe Verdi’s final opera, Falstaff, the perennial Shakespearean favorite through the ages is about to have that inflated view of himself severely tested as he with unashamed gluttony pursues not one, but two wealthy, married women – women who will turn out to be much the more clever and creative in their own schemes to teach Sir John a lesson he will never forget – at least not until the next jug of mead he drowns down his massive gut.

To bring it sixty-third season to a close, West Bay Opera pulls out all comedic and tongue-in-cheek stops to present a Falstaff that is laugh-out-loud hilarious while also musically ‘Verdi-beautiful.’ Returning to Palo Alto for his eighth, annual production from his home base in Mexico City, Stage Director Ragnar Conde finds a host of ways to ensure the hilarity of Arigo Bonito’s libretto matches the magnificence that Music Conductor José Luis Moscovich attains from the ten principals, seventeen choristers, and twenty-six orchestra members (the last playing from five different locations/levels). The result is an evening of rambunctious and riotous revelry accented with a stage full of voices melodically glorious in a Falstaff where a smaller-than-usual operatic venue affords the audience up-close chances to feel as if we are right in the middle of all the trickery targeting poor, ol’ Sir John Falstaff.

Richard Zeller brings his big-sounding baritone into full play as he barrels through with rum-reddened nose the antics that his Sir John employs to set up his hoped-for duo-trysts with two women whom he believes “keep the keys to the money box” of their rich husbands. As John fills his belly while dreaming how to satisfy his lust for love, he is clearly also vested in filling his pockets with the gold he needs to continue his life of tavern luxury.

Everything Sir John does is hilariously over-blown and wonderfully over-done, from the voluminous layers of clothing he dons to the grand sweeps of his arms used to accent his words to a mouth that can open in cavernous proportions both to eat and to sing forth his propositions and promises. So intent is he on his own greatness and so hungry to appease his ever-gnawing appetite for a beautiful woman’s kisses and her husband’s gold that he is as blind as a bat to all the obvious schemes playing out around him that are meant as righteous and roisterous revenge for his own devilry of sending the exact same two letters of love to two women who are best of friends.

Taylor Haines and Veronica Jenson are the two desired flowers that Sir John hopes to pluck of their innocence and their money, playing Alice Ford and her friend Meg Page, respectively. The scene where the two friends first discover that each has received exactly the same letter as the other with only their names changed – letters with such Falstaff lines as “You are the merry wife; I am the merry conqueror” – becomes musically and comically a thoroughly entertaining mixture of mocking Sir John and of planning how to lure him into a trap he cannot escape. When joined by Alice’s other friend, Mistress Quickly, and Alice’s daughter, Nannetta, the four women join in intricately countering melodies as they push their plotting into firm plans.

As events unfold and schemes become ever more silly, Taylor Haines as Alice in particular has a number of opportunities to ring forth in her soprano brilliance that rises in its clarity and beauty above the farcical events on the stage itself. Sometimes cheeky, sometime coy, her Alice sings in just the right manner to fool Falstaff into believing she might actually love him while at the same time her voice and facials are laughingly declaring just how much a fool she knows he is. Notes flow displaying both the powerful strength of her character and the sureness of her abilities to outsmart the men around her. As it turns out, not only must she teach Falstaff that there is a Renaissance MeToo Movement bubbling up in her garden, but she must also do the same for her too-quick-to-distrust husband.

During a disguised move his wife has helped plot in order to fool Falstaff into a planned rendezvous with the Thames, Alice’s husband Ford gets himself caught up in believing that his wife actually is planning on a secret tête-à-tête with the balloon-shaped scoundrel. Krassen Karagiozov as Ford shows up at Falstaff’s chosen abode – the Garner Inn – in the guise of “Signor Fontana.” “Fontana” is a supposed admirer of Alice, offering greedy Falstaff a bag of gold to seduce a supposedly shy Alice in order to ready her for his own approaches. Ford’s “Fontana” employs wonderfully animated slyness to fool the gullible Sir John who almost slobbers in his anticipation of earning money for an illicit affair that he thinks he is already scheduled to have in the next hour.

The rich, rolling tones of Ford’s baritone explode with ignited punch once he believes Falstaff is actually going to have such an affair with his wife, reaching into impressive falsettos to express his mounting, quick-judged jealousy. The soon-to-be cuckolded husband that Falsetto had earlier jollily described to “Fontana,” is exactly the horn-wearing victim that the real Ford now believes himself to be. In this rip-roaring scene and in the ensuing shenanigans, Mr. Karagiozov continues to shine both musically and comically.

Playing major roles in setting up and executing the traps for Falstaff is Mistress Quickly, a name and persona Verdi borrows from Shakespeare, transforming Quickly from the Bard’s malapropism-prone inn-keeper and sometimes friend of Falstaff now to be a round and jolly lady of society and loyal friend of Alice. Patrice Houston is deliciously funny in her tempting seduction of Falstaff to fall not once, but twice to the fates of embarrassment he will undergo in the hands of her friend, Alice. Better yet, Ms. Houston’s deep and beguiling mezzo-soprano has a range fun and furious that varies from mocking mimics of the easily-fooled Falstaff to thunderous warnings of approaching doom when she scares Falstaff that Ford is about to discover him in the arms of Alice – all of course a pre-planned scheme to get the giant into an even-more giant basket of dirty laundry. Each time she is on the stage, Patrice Houston brings energy, frivolity, and vocals that reach down deep to tickle and to impress us as audience.

While all the hoopla, disguises, and grand chases are occurring in order to teach Falstaff a thing or two, Verdi and Boito have included a love story involving the Fords’ daughter, Nannetta. Father Ford is trying to shut down the love-birds while Mother Alice is intent that Nannette shall marry the man she loves and certainly not the old, rich nincompoop her husband has chosen (a stumbling, ridiculous Dr. Caius played with bumbling brilliance by Michael Mendelsohn). (Wouldn’t you think that Ford would finally realize his only fate is to be out-smarted by his more-clever wife?)

Anatasia Malliaras is one of the evening’s true joys vocally. As Nannetta, she time and again takes Verdi’s runs of trickling notes and brings joyous interpretations. Her soprano so easily glides, then hangs, and then ever-slightly trembles as she sings of her love for Fenton, played by tenor Dane Suarez who has moments of his own accomplished vocals but also seems somewhat strained in several of his passages.

In this finale of Verdi’s career, the role of the Chorus is not a major one; but when called upon, Chorus Master Bruce Olstad ensures the voices blend with style and sparkle. Chorus members really get to join in the fun in a full-on, frantic search where Ford thinks he is about to find Falstaff making love to his wife, just one more scene directed by Ragnar Conde that milks every opportunity to increase the gag and the frolic.

The three acts, each with two scenes, play out on a stage designed by Peter Crompton where a middle, drop-back section and steps up to its raised position provides some depth and variety possibilities as we move from inn to the Ford home to its garden and finally to Windsor Park. But it is in Peter Crompton’s Disney-esque animated projections that a major element of the evening’s hilarity and sheer ‘wow’ lies. A large portrait comes to life as its bearded resident makes faces watching Falstaff being fooled by Ford as “Fontana.” Huge, sculpted shrubs in the shapes of animals dance across the English gardens projected in the three-dimensions of the stage’s walls while skies beautifully change their hues as day proceeds through is stages of light and cloud changes. What cannot be projected on the walls populates the stage itself through the flasks, mugs, and even baguettes provided by properties designer Shirley Benson.

Abra Berman brings to yet another Bay Area stage her over-the-top creativity and jolly-good fun in designing the costumes of this Henry V era of England, having particular whimsy with those that the larger-than-life Sir John dons. Lisa Cross adds her period touches in wigs and make-up while Steve Mannshardt once again proves himself to be lighting designer extraordinaire. Finally, designer Giselle Lee has ensured both effects and balance of sound support the beautiful music of singers and orchestra as well as enhance the frolicking story.

As a long-time subscriber to San Francisco opera, I can attest it is absolutely a joy to attend a production by such a stellar company as West Bay Opera where the vastly more intimate setting of the Lucie Stern Center allows me to see clearly facial expressions without binoculars. To enjoy close-up the acting as well as the singing is an opportunity that all opera faithful should avail themselves. And for the die-hard musical-theatre buff who avoids operas, I can think of no better time to jump in and become opera-hooked than the Verdi opera that at the end of the nineteenth century clearly set the path for future musical comedies on Broadway and the West End.

Rating: 5 E

Read this and other reviews by Eddie Reynolds at:

https://theatreeddys.blogspot.com/2019/05/falstaff.html

- Read the review in artssf.com

TROUPE MAKING SILK PURSE FROM SOW’S EAR

June 3, 2019 Paul Hertelendy

The miracle of West Bay Opera is not just that they pulled off yet another highly professional show in Verdi’s Falstaff; it’s what they do bringing that tiny community theater never built for opera so vibrantly to life.

Consider that you have no overhead space for flying scenery, no prompter’s box, very limited stage depth, a pit that can’t even seat half a Verdi orchestra, and space even tighter than Falstaff’s drinking buddies usually are. The conditions would be enough to drive Verdi himself to drink right alongside them.

So with brass and timpani stacked one atop the other in the wings with elaborate closed-circuit TV from the podium and stunning high-tech video projections for scenery, somehow it works. At least, as long as the old fat knight Falstaff exhales mightily whenever squeezing off into the wings—as precarious a maneuver as, say, docking some trans-Atlantic dirigible just landed into your garage.

With WBO’s two-year Verdi festival in midstream, Falstaff brought out not only the new technology scenery but also the sharpest stage direction I’ve seen all season, via Ragnar Conde, a Mexican who has worked in six countries. He gave the merry wives of Windsor who dupe the lecherous old knight the meticulous detail in gesture and face that you’d give a Shakespeare play. And the title character, baritone Richard Zeller, is no buffoon—even after being victimized and thrown into the river to “avoid an outraged husband,” he regains a measure of dignity while dispensing forgiveness in his parting “All life is a jest!”

Casting and handling a well-balanced pro cast of 10 plus chorus is no mean feat. Impressive in the female lead was soprano Taylor Haines (Alice Ford), a tall woman with stage presence who could project well, even in a larger hall. And as the husband Ford around whom Falstaff maneuvers, we had the resonant baritone Krassen Karagiosov, best in his act-two aria of high agitation. He is fondly remembered for having provided the emergency voice (only) in the previous Verdi, “I Due Foscari,” when the lead baritone had been abruptly silenced by laryngitis. The show must go on!

Credit to the orchestra, pulling it together even though stationed nearly off in the parking lot. And of course to WBO General Director, José Luis Moscovich, the engineer of the marvelous resurgence of this 63-year troupe, who conducted with smart pacing.

As for the novel backdrop projections, under Peter Crompton’s direction: What appear to be static backgrounds intermittently move and spring to life, whether a Falstaff portrait suddenly gesticulating or topiary popping up out of nowhere.

THE AFTERTHOUGHT OF THE MOST AMAZING RETIREE OF ALL TIME—Verdi had decided to take to the rocking chair after Otello. But, just for his private enjoyment of Shakespeare, he wrote the Falstaff manuscript, never expecting it to be produced. Or so he claimed. But this latest and perhaps greatest of his many works came off his shelf and was premiered in 1893, the same year he turned 80. And just for a little challenge, he wrote an awe-inspiring fugue to be sung by the 10 soloists at the final curtain, requiring a diction as exacting as a Gilbert and Sullivan patter song.

TWO-YEAR VERDI FOCUS—Next season, three more Verdi operas will be featured.

Verdi’s opera Falstaff, in Italian with supertitles, closing out June 2 at the Lucie Stern Theatre, Palo Alto. West Bay Opera’s 63rd season finale; three hours. For WBO info: (650) 424-9999 or go online.

Read this and other reviews by Paul Hertelendy at

http://www.artssf.com/troupe-making-silk-purse-from-sows-ear/

- Read the review in the San Francisco Classical Voice

The old theater saw is true: tragedy is easy, comedy is hard. Verdi’s Falstaff is pure comedy. Falstaff simultaneously woos two wealthy ladies (Meg and Alice). They discover the deception — as does Alice’s madly jealous husband, Ford. Multiple schemes of vengeance lead to chaos, but Falstaff accepts his just deserts with good humor. Such a farce demands impeccable timing, tight musical coordination, strong directorial vision, and balanced acting. Those attributes are uneven in West Bay Opera’s current production, and the resulting show, while often impressive, simply isn’t very funny.

This Falstaff’s biggest comedic shortcoming lies in a self-conscious staging. Bardolfo’s large fake nose, the men’s over-rouged cheeks, and Ford’s spiked hair suggest an over-the-top approach. Badly photoshopped projected backdrops with distracting animation reinforce this. The acting is often pure mugging, especially when Alice and Meg are playing scenes for Falstaff’s benefit. The production keeps screaming that this is comedy — and that kills its comedic impact. Scenes feel freshest when the singers stop overacting: In Act I, for instance, Meg, Alice, Nannetta, and Mistress Quickly plot their revenge with delicious, unaffected relish.

That’s not to say West Bay Opera’s Falstaff isn’t worth hearing. Under the baton of WBO General Director José Luis Moscovich, the orchestra provided wry punctuation for the text. Dramatic, dark-hued strings set the midnight mood for the final scene perfectly (far better than the projected mist swirling on the backdrop). The difficult final fugue — (“Tutto nel mundo è burla” (Everything in the world is folly) — proved a musical triumph and ended the opera on an energetic note.

As usual, West Bay Opera served up a cast of singers worth hearing. Baritone Richard Zeller made his West Bay Opera debut as Falstaff. From his booming “honor” aria in the first scene to his tossed-off interjections of fear in the last, he commanded attention. Michael Orlinsky and Kiril Havezov were in fine voice as his graceless servants, Bardolfo and Pistola. Baritone Krassen Karagiozov stole scenes as Ford, with his dusky sound, smooth legato, and jealous rages. Soprano Taylor Haines’s Alice Ford sported a shimmering, varied tone and mischievous personality. She was ably supported in her schemes by Patrice Houston’s chesty-voiced Mistress Quickly and Veronica Jensen’s warm-voiced Meg. The opera’s young lovers get some of the most lyrical music. Dane Suarez’s bright tenor (as Fenton) and Anastasia Malliaras’s silvery soprano (as Nannetta) made the most of it.

Dragging down the overall professionalism of the production was a lack of attention to detail. A misspelled title (‘Fallstaff’) and badly timed supertitles frustrated me, as did the aimless milling about and general listlessness of the chorus in the final scene. The placement of the brass section onstage made their entrances startle and their long lines compete with the singers. Otherwise-elegant women’s costumes were ruined by a petticoat shortage, leaving hoop lines showing through skirts and bare skin peeking out from beneath hems.

Falstaff is an ambitious programming choice for any opera company. It has all the musical challenges of Verdi without the name recognition to bring in audiences. It’s a dramatically tight piece: Every word and note serves the plot. But that plot can seem frivolous if the characters treat it all as a game, without emotional stakes. Ultimately, that’s where West Bay Opera’s Falstaff falls short. I laud their ambition and the musical talent they have brought together. Unfortunately, it’s unclear what those are in service of: This Falstaff does not provoke many laughs, or have much to say.

Ilana Walder-Biesanz reviews opera and theater for San Francisco Classical Voice, Opera Online, Bachtrack, and Stark Insider. She studied in England as a Gates-Cambridge Scholar (European Literature and Culture) and in Germany as a Fulbright Scholar (theater studies).